Doug Hadden, EVP Strategy and Innovation

The lack of integration in financial management information systems (FMIS) imperils global public finances, causing challenges for governments and negatively impacting citizens. In this post we’ll examine this from a number of angles, covering:

- How the lack of interoperability imperils public finances

- The state of FMIS integration

- Why “integration” is not sufficient

- Towards a precise understanding of “interoperability”

- Why traditional integration solutions are not enough.

1. How does the lack of interoperability among government financial systems imperil public finances?

Governments implement core FMIS systems to handle treasury and commitment accounting functions. But they also have a range of government financial subsystems, including asset, debt, payroll, procurement, social support, and taxation systems. The lack of integration across this software portfolio:

- Creates inconsistent decision information, often known as “multiple versions of the truth”

- Introduces errors while reducing timeliness through manual intervention and poor interface practices

- Reduces compliance for public finance processes including overspending and arrears

- Compromises public finance planning, forecasting and early warning systems.

The impact of these issues are wide-ranging, and you’ll see the lack of integration as a major factor in poor Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability (PEFA) assessments. Lack of interoperability affects:

- Budget reliability, as a lack of integrated planning for credible budgets is followed by poor controls resulting in large variation between budget plans and outturns

- Transparency of public finances, because a lack of shared public accounts classification compromises budget documentation and makes fiscal transparency difficult

- Management of assets and liabilities, as insufficient integrated risk management across standalone debt, asset and public investment systems, compromises government liquidity and national development strategy outcomes

- Policy-based fiscal strategy and budgeting, due to a lack of planning coordination and integration with government goals like national development strategies and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

- Predictability and control in budget execution, because inconsistent data, and the lack of shared controls across financial subsystems, results in lack of predictability

- Accounting and reporting, due to poor data integrity resulting in a long process and timeframe to close yearly books with late reporting

- External scrutiny and audit, because insufficient interoperability means a lack of consistent data to facilitate audits and scrutiny.

2. What is the state of FMIS integration?

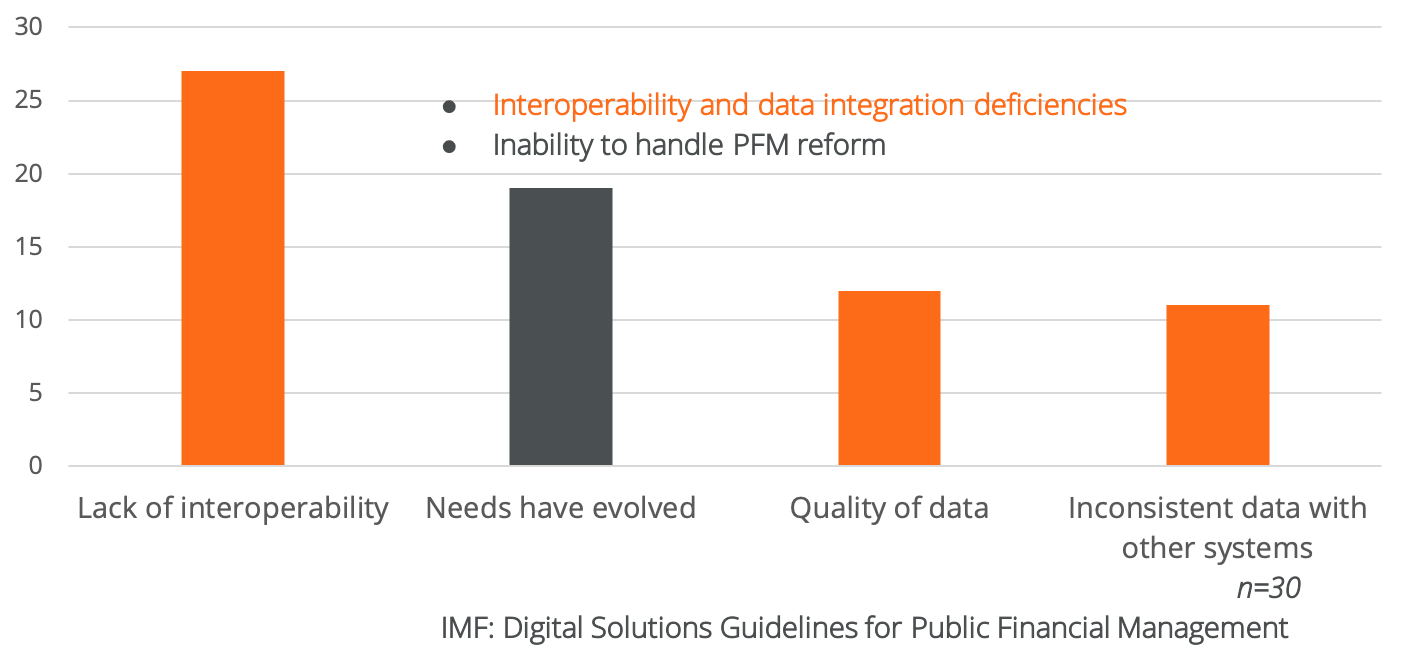

A recent IMF study, Digital Solutions Guidelines for Public Financial Management from Lorena Rivero del Paso, Sailendra Pattanayak, Gerardo Uña and Hervé Tourpe highlighted integration and adaptability constraints in FMIS within emerging economies. Here’s a subset of important factors:

27 of 30 countries surveyed reported a lack of FMIS interoperability. My view is that this lack of interoperability also leads to poor data quality, inconsistent data, and, in practical terms, multiple versions of the truth. The IMF study suggests that “the main reasons for such siloed structure are (1) lack of collaboration across government agencies, (2) absence of a data governance policy and/or inadequate recognition of the strategic value of fiscal data, and (3) legacy IT systems that pose challenges for interoperability with newer systems.”

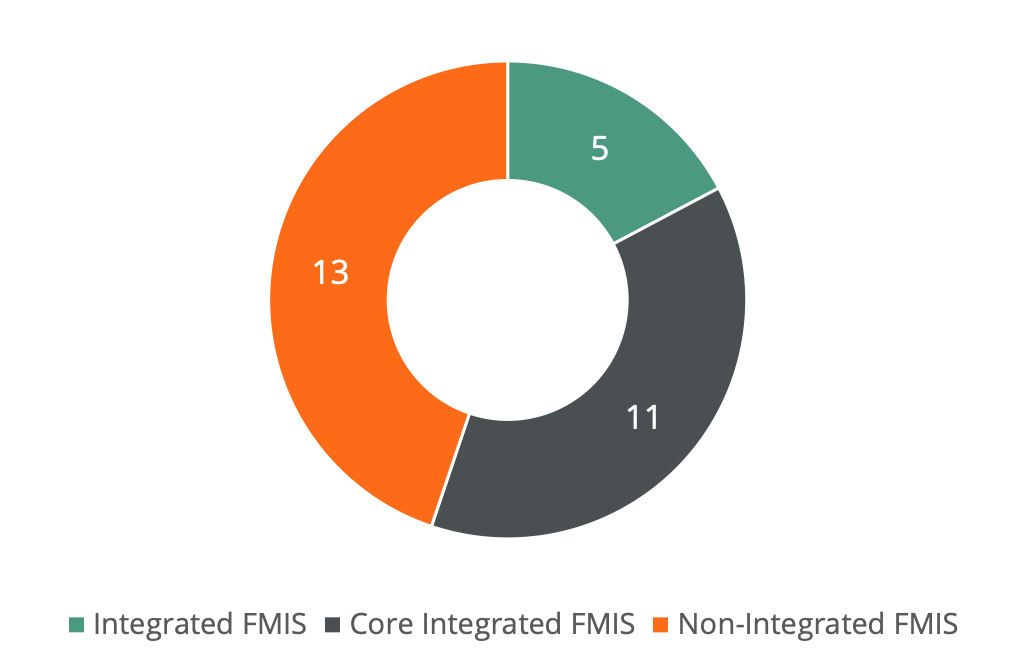

Integration is not much better in advanced economies according to an OECD study from February 2024, Financial Management Information Systems in OECD Countries, where 13 of the 29 countries studied used a non-integrated FMIS:

Interestingly, the OECD study observes many of the same characteristics as the IMF even when systems are integrated: “a large number of OECD countries with integrated financial management systems rely on legacy IT systems to support their financial management functions.”

3. Why is “integration” not enough?

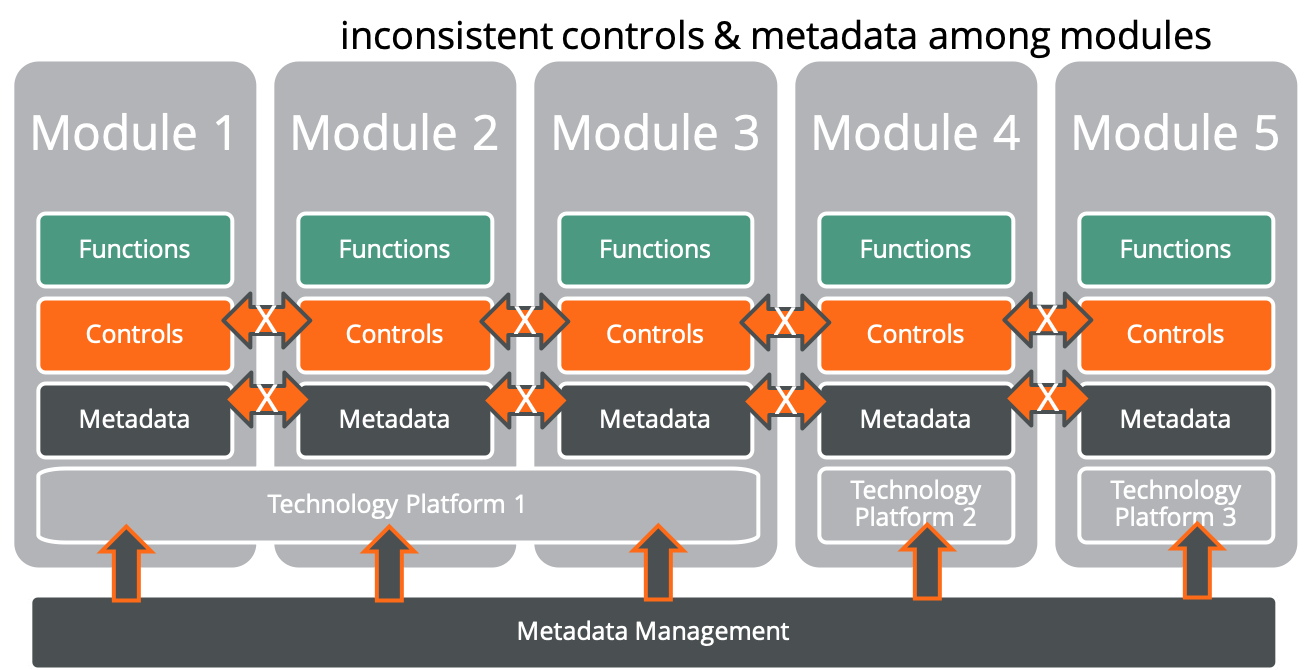

The notion of “integration” is often thought to be primarily data integration. For example, data from payroll, procurement, or tax administration systems could update the FMIS. Scripts and metadata management is often used to facilitate these interfaces.

But the difficulty with these traditional approaches is that metadata management rarely makes for subsystem semantic consistency. Put simply, the data may be exchanged, but the bigger picture intention is not. Government goals that are captured in Charts of Accounts (CoA) rarely inform payroll, procurement or tax administration systems. For example, the importance of revenue mobilization for the procurement of public investments is rarely captured in tax administration systems. Value-for-money calculations used in procurement systems are not aligned with national development strategies. And government performance goals are not aligned with talent management payments and promotions.

What’s particularly missing in the integration argument is controls. Budget, commitment, and segregation of duties controls are rarely consistent across budget cycles. Payroll, procurement, and tax administration systems are rarely budget aware. This results in wage bills which exceed budgets, procurement contracts where multiple-year commitments and budget roll-over rules are not monitored (and so exceed budgets), and tax arrears which are rarely visible to government treasuries.

4. Can we get closer to a more precise understanding of interoperability?

Traditional concepts like “seamless integration” or “standard taxonomy” do not cover the needed scope of interoperability. That’s because interoperability covers more than technology. An interesting paper by Györgyi Nyikos, Bálint Szablics, Tamás Laposa, Interoperability: How to improve the management of public financial resources gets to the heart of the issue, and defines the necessary levels of interoperability for premium effectiveness:

- “organizational interoperability ensuring the formalization of the processes (modelling) and the interoperability of the models and the harmonisation of administrative systems (i.e. it has several normative elements). Interoperability at organizational level prefers multilateral solutions for everyone instead of bilateral solutions;

- functional interoperability meaning the ability of systems to exchange data with each other where the provider issues data that can be interpreted;

- semantic interoperability ensuring the use of common descriptions of exchanged data;

- technical interoperability ensuring the introduction of necessary information systems environment to allow an uninterrupted flow of bits and bytes (technologies, standards, policies);

- legal interoperability ensuring that legislation does not impose unjustified barriers to the reuse of data in different policy areas, guarantees the regulatory background where the cooperating organizations have the appropriate legal power to implement the data exchange in line with common standards. Since public administration can only perform an interoperability act after ex-ante legislation is in place, ensuring this component is an elementary condition;

- political interoperability provides the central power and support to achieve implementation and management of public administration interoperability. Here, we can differentiate both national and international dimensions.”

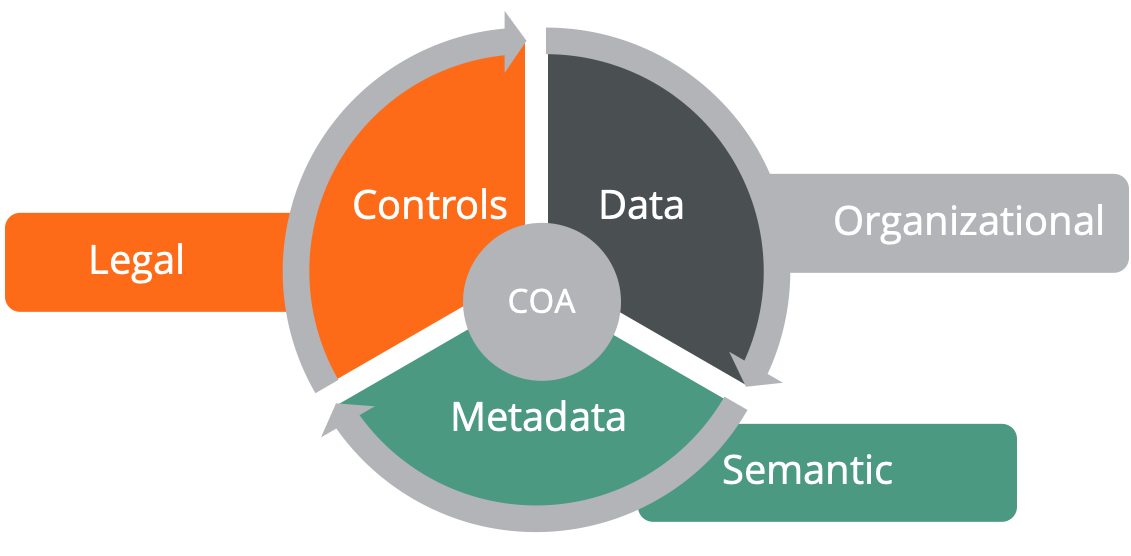

So how can we take this theoretical definition and apply it within an FMIS? My key observation is that the Chart of Accounts (CoA) represents the taxonomy for interoperability. This is because the CoA acts as the:

- semantic heart, or metadata, of government

- underlying target for functional interoperability

- integrator of legal and political interoperability showing organizational structures, controls, and program budgeting

- main control object for all public finance.

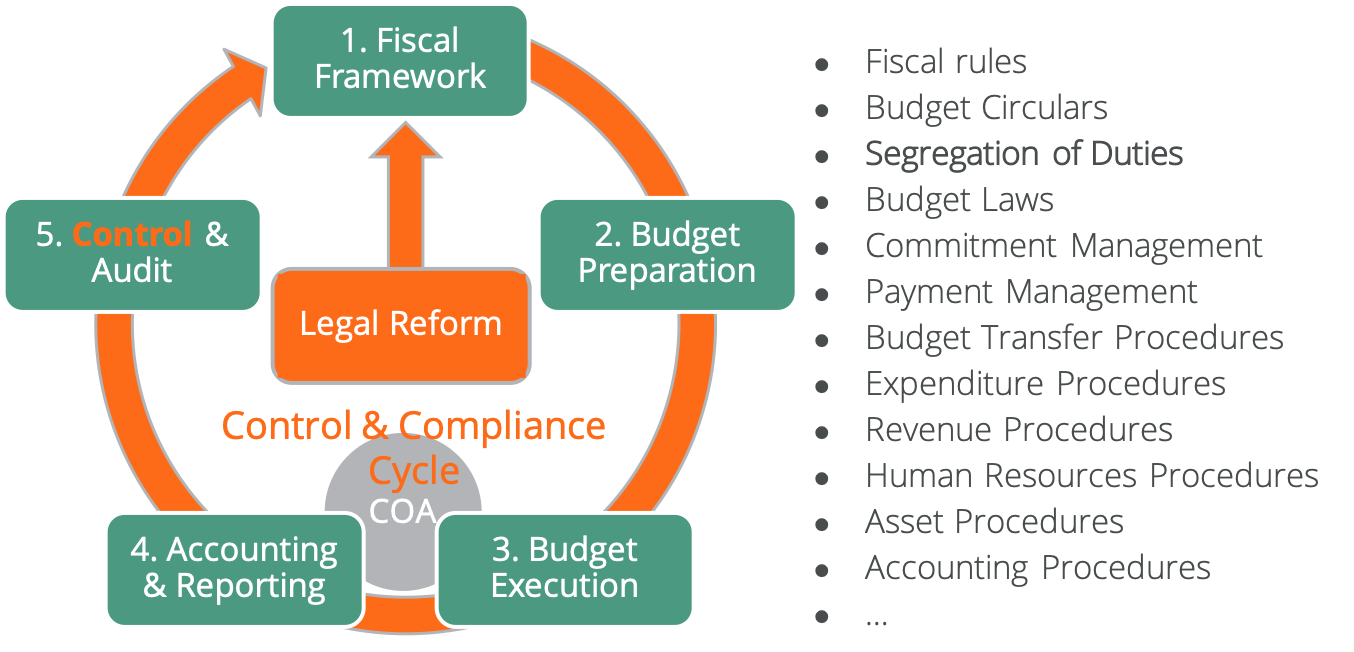

Another way to look at the impact of the CoA is shown above:

- Chart of Accounts, in grey, is at the heart of controls, data, and metadata aligned to organizational structures

- Data for technical integration, in black, is informed by the CoA metadata

- Metadata, in green, provides the semantic information

- Legal, in red, provides the necessary controls based on the CoA.

This interoperability via the CoA covers the entire government budget cycle, as shown below. The CoA provides consistent control and compliance across the entire budget cycle for interoperable systems. The standard budget cycle diagram places “control” with “audit” in step 5. Automated and integrated controls should be present at every stage of the budget cycle for interoperability.

My view is that Nyikos, Szablics, and Laposa have the most effective definition for PFM interoperability that informs FMIS interoperability. And, organizational interoperability is particularly important because there are often few technology related issues to support integration. Legacy integration methods can be used. Many governments fail to act on technology integration because of organizational barriers and resistance to change.

5. Why are traditional “magic bullet” approaches not enough?

You’ve likely heard “magic bullet” technology solutions to challenges with interoperability. These often include tools such as application programming interfaces (API), enterprise metadata management (EMM), enterprise services buses (ESB), extraction, transformation and load (ETL) and open source software. However, these approaches can be part of a data governance solution, but are ineffective for controls governance affected by PFM reform. And, data governance requires attention because:

- APIs and standard interfaces often break when software is updated

- EMM and ESB scopes usually extend beyond PFM adding complexity

- ETL is often predicated on legacy interfaces and direct database calls generating metadata mismatches, and is primarily used for reporting and dashboards rather than process integration

- Open source middleware is well-established and robust while supporting integration standards, however open source application software is expensive to adapt and maintain for the government domain.

The mismatch between PFM business and technical architectures adds friction to interoperability. However, upfront work for data and controls governance can simplify interoperability, and mitigate the risk of problems. Here are some suggested steps:

- Create shared organizational understanding by tying systems to government priorities

- Build the CoA as the key metadata taxonomy and controls structure from the outset, but recognize the CoA will need to change over time to reflect PFM reform, as a point in time solution will not meet governmental needs in the long term

- Leverage integration technologies, but expect challenges for upgrades and updates so that these can be planned for ahead of time

- Evaluate integration risks with legacy technology. Often the cost to maintain these systems and interfaces exceeds the cost to upgrade.