What is the Smart Cities hype gap?

Observers have come to question whether smart cities enhance citizen quality of life. Some have gone so far as to question the wisdom of the smart cities concept. “Major cities claim to be “smart”, seminars and conferences pop up everywhere and the “smart” -label is attached to all sorts of technology, and many people start to believe the smart city rise is a mere empty hype. When asked about it, by The Economist, 46% agreed smart cities indeed are a hype, and 54% voted against it. (Janson 2014)”

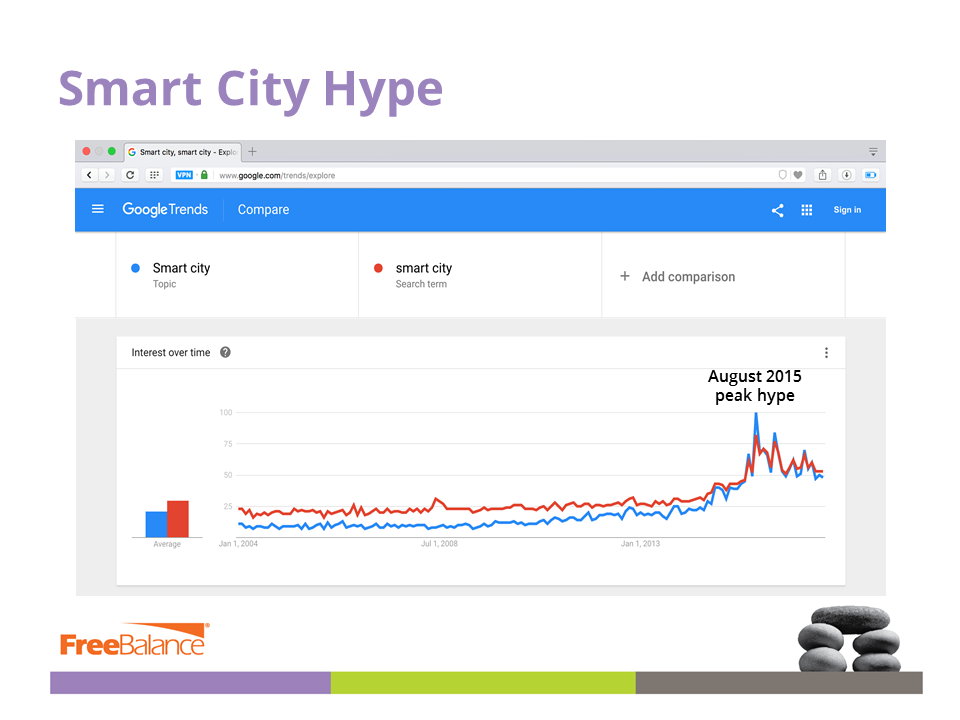

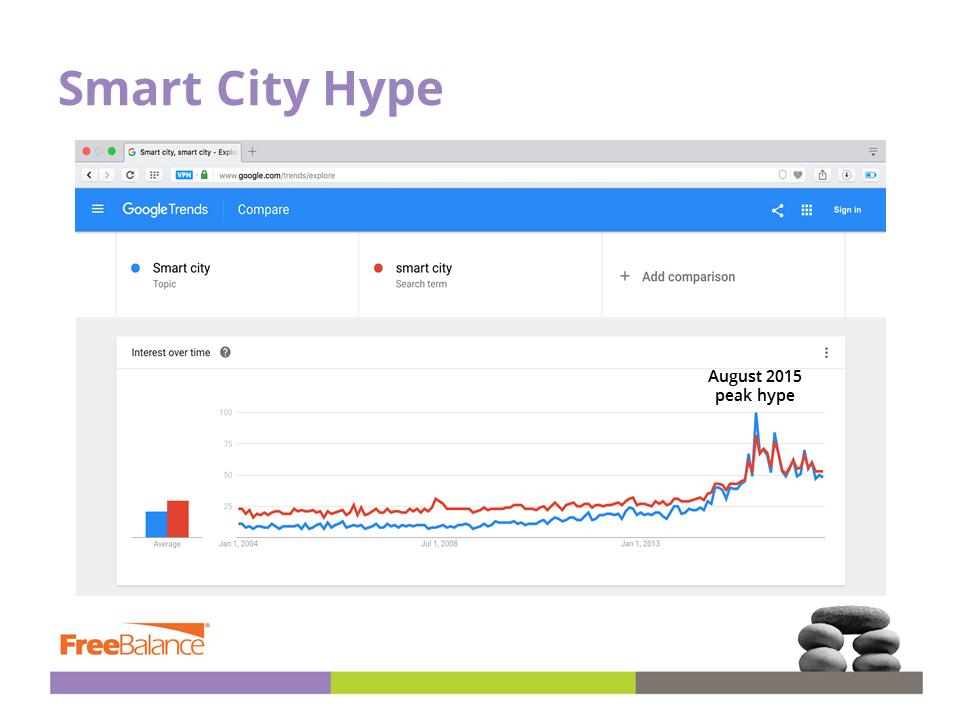

The gap between the smart cities hype and the smart cities reality appears to be narrowing since peak hype in 2015.

Smart cities have become a catch-all solution for what ails the urban environment. “Overnight, smart cities have transitioned from being mere novelties, to serving as examples of technology application, to becoming principal targets of urban policy. (Glasmeier and Nebiolo 2016)” It “has emerged triumphant as a model and social theory, integrating or co-opting previous narratives (sustainability) but using the usual claims (bureaucratic planning and better management of urban development). (Fernández 2016)”

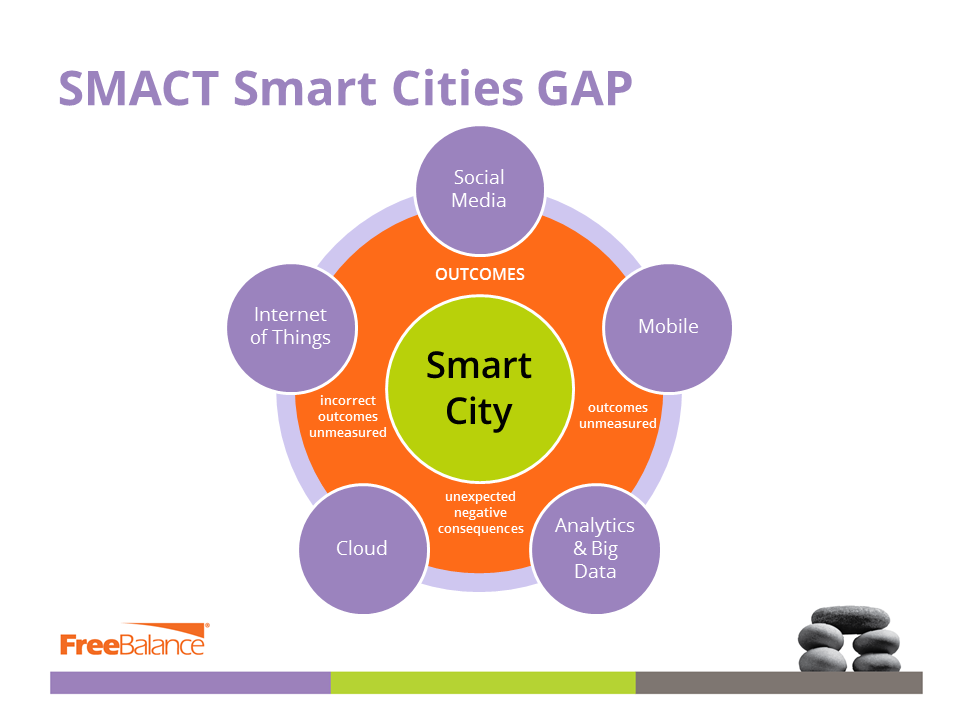

Technology has been the focus of smart cities hype. The combination of SMACT (Social, Mobile, Analytics, Cloud, Internet of Things) technologies is seen as enabling cities to achieve cost effective social benefits. However, “the advocates of smart cities have often faced criticism: for being too concerned with hardware rather than with people; too focused on finding uses for new technologies rather than finding technologies that can solve pressing problems; and for emphasising marketing and promotion at the expense of hard evidence and testing solutions out in the real world. (Saunders and Baeck 2015)” The real world for cities is complexity. It is a complex set of social urbanization challenges and opportunities.

A more holistic approach to smart city projects is to consider citizen impact. There is rising evidence of the value of considering well-being and quality of life in public policy. This has the ultimate political incentive – re-election “in European elections since 1970 the life satisfaction of the people is the best predictor of whether the government gets re-elected – much more important than economic growth, unemployment or Inflation. (Clark, Fletch, Layard et al 2016)”

Policy makers should consider citizen quality of life and well-being when selecting, monitoring and measuring smart city projects.

What is the citizen well-being promise of smart cities?

“Smart Cities promise improved quality of life for the world’s estimated 3.9 billion urban dwellers while at the same time allowing better, more efficient use of resources and improved security, (Bird 2016)” and “growth, jobs and decarbonisation [in the] global market for Smart Cities solutions [of] 1.3 trillion € in 2025 (Market Place of the European Innovation Partnership on Smart Cities and Communities 2017)” “The ultra-modern consumer technologies available today have radically transformed the lifestyles of city dwellers (Rajan, Black, Chinta, Clark 2016), acts as a technology underpinning for improving the quality of life.

The use of technology promises to improve citizen health and wealth

- Smart Transportation and Smart Power Grids to reduce pollution

- Smart Health, Smart Water and Smart Sanitation to prevent health issues from occurring

- Smart Education and Smart Infrastructure for city growth and innovation

- Smart Public Safety to reduce crime and improve disaster resilience

Is there a lack of evidence that smart cities technology benefit citizen well-being?

The outcomes of smart cities projects are yet to be known. The evidence suggests “not all smart city projects are having completely positive effects. (Smith 2016)” This is not unusual in nascent technology markets, particularly when dealing with many one-off experiments in complex systems like cities. Social factors of smart cities might be the most difficult to measure, (Edell 2016)” while outputs without context are likely the easiest.

Smart cities represents a policy challenge of “experimenting based on vague hunches when there are equality meritorious uses of scarce resources that in the immediate moment improve vital and yet more conventional concerns such as cleaner, safer better lit streets (Glasmeier and Nebiolo 2016)” The hype means that “despite its totalizing ambitions, the debate on smart cities has been very limited, biased, incomplete and precipitate. (Fernández 2016)”

Smart city hype has manufactured an unusual reference frame of hyperbolic promise in the face of limited progress. Enthusiasm has created unrealistic expectations from the menu of smart city technology offerings. There is a better policy approach by recognizing technology maturity. Policy makers can:

- Recognize that experiments are necessary in pursuit of lofty goals, and some may fail

- Leverage agile methodologies that enable consistent improvement at low cost

- Determine strategic objectives and find improved ways of measurement over time

- Mobilize citizens, using open government, to identify root causes and prioritize investments

Are smart cities vanity projects?

Smart city grant contests, third-party “smart” ratings, and politicians touting future benefits for investments has created a new urban arms race. This new competition to attract talent and growth as created has become a magnet in emerging economies. “Few buzzwords raise as much excitement among leaders in the emerging world, who hope to turn their traffic-clogged megacities into pristine recreations of Singapore or Barcelona. (Crabtree and Abraham 2016)” There is something very attractive in this concept of “smart”. Yet, it seems that many smart city initiatives are “more talk than action….it’s implementation has been very shallow. (Economic Times, 2017)”

We should not be overly concerned about the positive political currency around smart cities. There are political incentives beyond vanity and looking good. Making cities look good has value. “Political leaders want their cities to rise up smart city rankings; they believe that smart cities will be attractive places for people and businesses to move to. (Saunders and Baeck 2016).” The alternative could be to under-invest in technology that can help cities to achieve sustainable growth. The danger is that the hype is leading to citizen expectations of immediate positive returns while the smart city promise is long-term, much like any public investment.

Are technology firms, rather than citizens, the beneficiary of smart cities projects?

Technology vendors have been responsible for creating hype. That is what technology marketers do.

“Utopian, urban visions help drive the “smart city” rhetoric that has, for the past decade or so, been promulgated most energetically by big technology, engineering and consulting companies. (Poole 2014)” It might be time for vendors to dial down the hype. “Egged on by swarms of technology companies and management consultants, these visions of technological utopia face a real risk of turning into expensive delusions. (Crabtree and Abraham)” “Many of the champions of these early smart cities were IT companies who knew a lot about advanced networking technologies and data analytics but little about how cities work, which is why they focused on building new cities from scratch rather than engaging with the issues actual cities face. (Saunders and Baeck 2015)”

The smart city technology market consists of a wide range of vendors including telecommunications, electronic control equipment, enterprise software, consulting, clean tech, open government and specialist companies. Some of these vendors compete in legacy technology, causing some to ask whether smart cities are “a new replacement market for vendors that are otherwise facing slowing rates of growth in and competition for their traditional commercial markets, or is it a transformative conception that is leading to future and better forms of urbanization? (Glasmeier and Nebiolo 2016)”

Consulting and systems integration form the largest part of the smart city technology market because of complexity and lack of industry standards. Large private sector firms often enter into Public-Private Partnerships with cities. The danger is that privatization, including PPPs “makes the provision of essential services – once the preserve of the welfare state and local governments – dependent on the whims of corporations and their business models. (Morozov 2016)”

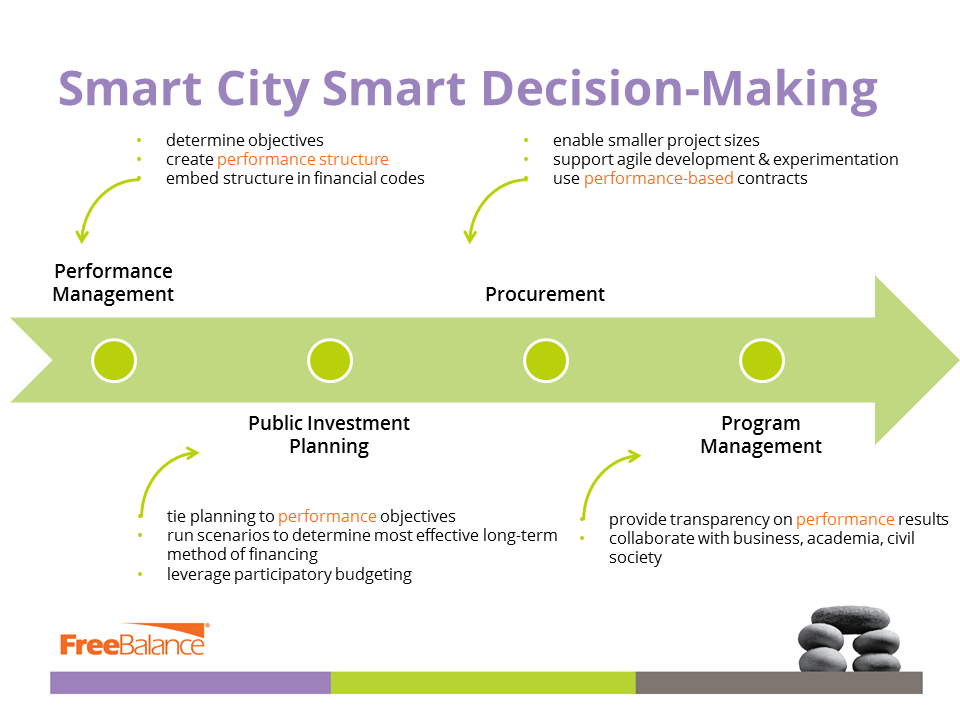

This is a governance challenge partly precipitated by public sector funding constraints. Annual budget and election cycles creates an incentive for short-term thinking. There is a need for “smart decision-making, smart administration and smart urban collaboration (Meijer and Bolivar 2015)” in the selection and governance of smart city projects.

Smart decision making for city governments include:

- Performance management to identify urban well-being objectives and strategy to drive smart city investments

- Procurement reform to enable smart city experiments using agile concepts, and learning to improve smart city investment outcomes through performance-based contracts

- Scenario modeling during public investment planning to identify the best long-term financing options and set output and outcome objectives, and leverage participatory budgeting to validate performance criteria

- Program management for smart city projects for collaboration among vendors, academics and citizens to improve outcomes, including feedback on the impact on citizen well-being

How can cities achieve well-being through smart city technologies?

“The unintended consequence of smart city “making” is to privilege technologies without equivalency tests that make clear what the public values are and what the basic needs are that these values seek to promote. (Glasmeier and Nebiolo 2016)” This needs to change. Fortunately, the market has matured from peak hype.

Cities do not become smart through the application of smart city technology. “At a deeper level, excitement about smart cities tends to rest on the misapprehension that digitising something makes it smart. Technology can play a role in making cities more liveable, but it is a means to that end, not an end in itself. (Crabtree and Abraham)”

Policy makers have the opportunity to upturn the model of smart city technology acquisition from technology to well-being. It is true that monitoring well-being is challenging, as it is with any measurement of government performance. “The big open question remaining is how to correlate the numerical results of indices with the real perception of quality of life. How is the transition possible from the objective measures of smartness to an intangible entity of wellbeing? (Dotti 2016)”

References

Bird, K. Enabling sustainable and smart cities for improved quality of life. ISO, July 15, 2016. http://www.iso.org/iso/home/news_index/news_archive/news.htm?refid=Ref2103

Clark, A; Fleche S; Layard, R; Powdthavee, N; Ward G. Origins of happiness: Evidence and policy implications. Vox, December 12, 2016. http://voxeu.org/article/origins-happiness

Crabtree, J; Abraham, R. The smart city delusion. The Strait Times, June 14, 2016.http://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/the-smart-city-delusion

Dotti, G. How to Measure the Quality of Life in Smart Cities? Phys.org, April 12, 2016. http://phys.org/news/2016-04-quality-life-smart-cities.html

Edell, T. Are smart cities just a utopian fantasy? TechCrunch, November 4, 2016. http://techcrunch.stfi.re/2016/11/04/are-smart-cities-just-a-utopian-fantasy/

Fernández, M. An urbanizing world and one size fits all solutions. CitiesToBe, 2016. http://www.citiestobe.com/article/an-urbanizing-world-and-one-size-fits-all-solutions

Glasmeier, A; Nebiolo, M. Thinking about Smart Cities: The Travels of a Policy Idea that Promises a Great Deal, but So Far Has Delivered Modest Results. Sustainability, November 1, 2016. http://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/8/11/1122/htm

Janson, K. Smart City: our future or empty hype? Smart Circle, March 12, 2014. http://www.smart-circle.org/smart-city/smart-city-future-empty-hype/

Meijer, A.; Bolivar, M.P.R. Governing the smart city: A review of the literature on smart urban governance. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2015. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0020852314564308

Morozov, E. Only a cash-strapped public sector still finds ‘smart’ technology sexy. The Guardian, September 10, 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/sep/10/only-public-sector-finds-smart-technology-sexy

Poole, S. The truth about smart cities: ‘In the end, they will destroy democracy’. The Guardian, December 17, 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2014/dec/17/truth-smart-city-destroy-democracy-urban-thinkers-buzzphrase

Rajan, R; Black P; Chinta, K, Clark, R.Y. Future Cities: Time to Smarten Up. IDC, July 2016. https://cdn.hpematter.com/Future-Cities-Time-to-Smarten-Up.pdf

Smith, K. Smart cities could change the way we live, but they must benefit everyone. World Economic Forum, November 3, 2016. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/11/smart-cities-could-change-the-way-we-live-but-they-must-benefit-everyone

—-Roadmap 2016. Market Place of the European Innovation Partnership on Smart Cities and Communities, January 27, 2017. https://eu-smartcities.eu/sites/all/files/Roadmap%20EIP_SCC_WEBSITE.pdf

—-Smart cities are more talk than action: Azim Premji. The Economic Times, February 4, 2017. http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/implementation-of-smart-city-project-has-been-shallow-wipro-chief-azim-premji/articleshow/56971850.cms

—-Smart Cities, How rapid advances in technology are reshaping our economy and society. Deloitte, November 2015. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/tr/Documents/public-sector/deloitte-nl-ps-smart-cities-report.pdf