There is rising interest in improving public investment planning and public investment management. The management of long-term capital public expenditures is seen as a critical contribution to sustainable growth. This rising interest in public investment management includes finding better automation and management through the use of Government Resource Planning (GRP) enterprise software. This is the third part of a series that explores:

- Why is public investment management crucial?

- How can software enable the public investment lifecycle?

- Why is integration among public investment software systems and subsystems important?

- What software solutions are available from FreeBalance to assist government in managing public investments?

Why is integration among public investment software systems and subsystems important?

Government organizations often use stand-alone software to manage the Public Investment Management (PIM) lifecycle. As described in the previous entry, a comprehensive PIM software solution requires elements of CPM, PPM, GRP, ERP, and SCM categories. Our observation is that the Commercial off-the-Shelf (COTS) and custom developed software used by governments for public investments is rarely integrated or interfaced in any automated fashion. Many specialists believe that standalone software is appropriate for what appears to be standalone functions, often used exclusively by single government agencies or ministries.

Standalone systems fail to meet the compliance, consistency, collaboration, comprehensiveness and communications needs of public investments. Here are some examples that we have seen in government implementations that lack integration:

- Separation of capital budget planning or procurement from performance structures resulting in investments that are not tied to government objectives

- Separation of operating and capital budget planning software resulting in lack of operating and maintenance budgets when the capital investment is completed resulting in crumbling infrastructure or hospitals and schools without supplies

- Separation of budget planning and budget execution resulting in the inability to pay for multiple year contracts because multiple year commitments were not integrated

- Separation of budget and cash planning resulting in poor cash forecasting and the need for more debt instruments to fund projects

- Separation of budget and debt management resulting in insufficient funding for public investments through poor forecasting, or stalled infrastructure projects because of lack of funds

- Separation of procurement from commitment controls resulting in exceeded or underspending budgets, breaking budget laws, and plunging governments into arrears (particularly if using cash-based accounting)

- Separation of procurement from contract management resulting in vendor payments that do not follow contractual requirements or financial regulations

- Separation of asset management from budget planning resulting in the inappropriate use of assets, like fleets, and the lack of budgets for operations, repairs and asset replacement when at the end of useful lives

- Separation of M&E from project implementation and operations where decision-makers and the public have little idea of the positive results from infrastructure investments

- General lack of segregation of duties where individuals are able to approve much of the PIM cycle without effective oversight – this often enables corrupt practices

Any large organization with multiple applications can benefit from strong integration. The primary risk for non-integrated systems is handling metadata changes. This is particularly important in the public sector with Public Financial Management (PFM) reform and modernization. Metadata, in this case, refers to information classifications that need to change across multiple applications. This can be particularly difficult when some applications have hard-coded metadata. There are coordination problems even in situations where metadata can be adjusted among many PIM subsystems. Examples of metadata issues that can touch many PIM subsystems from PFM reform include:

- Program budgeting where an additional COA segment is added to enable viewing information by programs rather only through the organizational structure

- Performance management where an addition COA segment is added or the program segment is updated to support performance structures aligned with government goals

- Accrual accounting where additional accrual COA elements are required and asset valuation and depreciation are tracked

- Procurement reform where new rules for commitments, contracts, vendors and payments require new classifications

- Cash management with the Treasury Single Account (TSA) that changes the nature of debt planning and payment management

How to evaluate integration needs

Some observers will argue that risks from lack of integration is not high in some cases. It is difficult to integrate a portfolio of COTS and custom-developed software that use different programming frameworks and use different mechanisms for integration. We have seen governments utilizing many poor technology practices for integration including stored procedures and direct database calls.

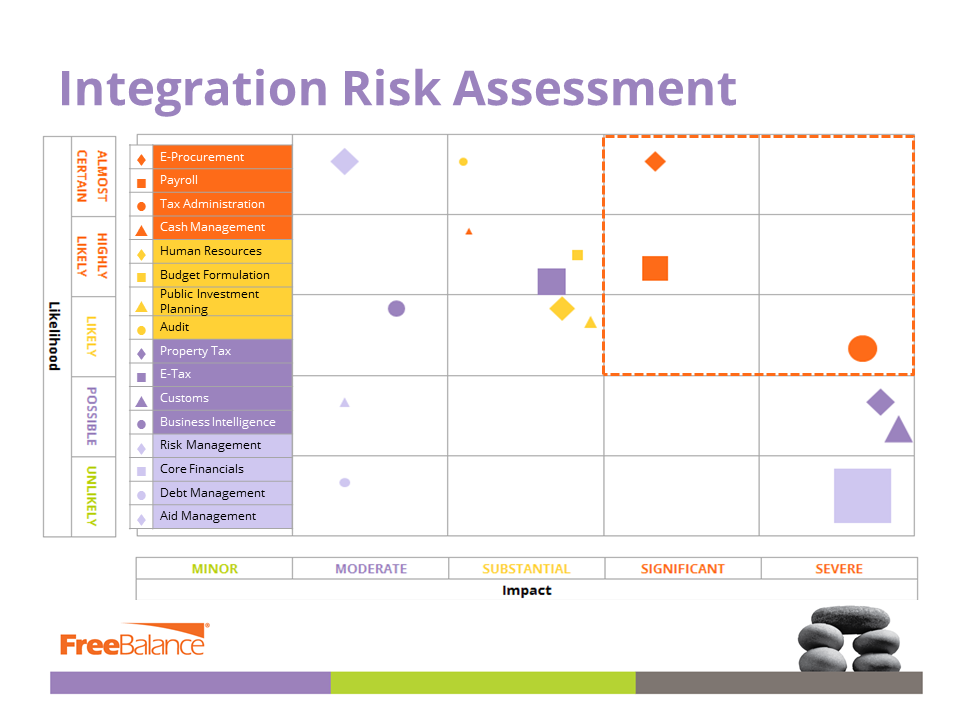

FreeBalance has developed a risk-based approach for determining integration risk. This uses a standard risk matrix showing impact by probability. Lack of integration risk increases for any application that:

- Lifecycle: touches many elements of the lifecycle from planning to results

- Logical integration points: touches many logical integration points with other applications

- Logical applications integration: touches many applications with the logical integration points

- Category applications: are part of a set of separate applications for a general function, such as multiple budget planning applications for salary, capital, recurring, development and debt budgets

- Commitment cycle: includes multiple steps in the commitment cycle from budgets to payments through commitments and obligations where budgets can be exceeded

- Error risk: includes large volumes of data like purchasing or large currency amounts like contracts

The process that we use identifies PIM subsystems risks from very high to very low:

- Very high: high likelihood and high impact where good practice tight technical integration is necessary, and where lack of integration capabilities combined with any lack of functionality results in application replacement

- High: either high likelihood or high impact combined with medium likelihood or medium impact, where an integration plan is necessary and application upgrades may be required

- Medium: medium likelihood and medium impact, where an enterprise architecture view of integration is necessary for all medium to very high risks, and applications are migrated to an application server bus

- Low: applications with lower risk can be interfaced using flat files, database calls or other simple mechanism and those applications rated low and medium risk should be replaced with integrated applications only if important functionality is missing

A procurement integration problem scenario

We outlined the reasons why standalone E-Procurement systems are not a good idea in a post in 2014. The integration points between procurement and other PFM subsystems were described. The post stemmed from a meeting with a team developing a custom “electronic Government Procurement” (e-GP) system. The team leader contended that the back-office GRP system would be able to handle commitments because individual ministries would ensure that there was budget before approving any purchase requisition or purchase order. He also suggested that there was no such thing as “back-office procurement.” The team displayed high confidence in these assertions. This reminded me of the saying: “confidence is that feeling you get just before you fully understand the problem.” Here’s the problem:

- Government agency checks to ensure that there is sufficient budget for a requisition of $10M for a public investment and issues a commitment (or pre-encumbrance) in the back-office system and issues a Request for Proposal in the e-GP system

- The commitment may not be strictly related to the procurement because the control is manual

- Vendors provide proposals where the winning proposal may be lower than the budget requiring a manual de-commitment in the GRP, or could be higher than the budget requiring budget approval that follows the fiscal discipline procedures used by the government

- The contract and implementation is likely to cover multiple years, hence the need to show multiple year commitments in the GRP and the budget planning system, and where the amounts for the years are likely to be different than the original plan

- The vendor or vendors execute the contract but there could be delays meaning that budget rollovers may be required, assuming that these are valid in the procurement law

- Goods and services receipts and returns need to be considered in the back-office GRP

- Penalties and performance payments could be part of the contract that affects the back-office calculation for commitments and budgets

- Lack of segregation of duties in the e-GP system, particularly if that system is responsible for authorizing payments, is a significant risk