In the latest of a series of posts reflecting on October’s IMF/World Bank annual meetings in Morocco, we share key takeaways and observations on the topic of public investment management.

Polycrisis or permacrisis?

Listening to the wide range of speakers across the week-long event brought to mind the joke about the pessimist and the optimist:

- Pessimist: “things are very bad”

- Optimist: “it’s going to get much worse”.

And both parties would agree on the key conclusion: much-needed social support is being constrained by high public debt in many countries.

Furthermore, lurking on the horizon are more complicating factors:

- Climate disasters

- Crumbling infrastructure

- Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) which, at present, seem unreachable.

We’ve written about how digital Public Financial Management (PFM) can reduce debt and improve social support in previous articles: in short, we need to do more with less. But what about addressing long-term resilience? How do we collectively ensure that countries around the world are ready for unexpected challenging situations, rather than reacting after the fact each time?

This is particularly important because these lurking risks are not disconnected from the current global crisis situation. In fact they are intertwined.

What are the critical public investments for resilience against future crises?

Preparing for future crises means reducing existing infrastructure gaps. Climate adaptation, climate mitigation, “build back better”, and “smart” infrastructure all lead to sustainable development. Among the public investment management contributions to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are:

- Clean water and sanitation (SDG 6)

- Affordable and clean energy (SDG 7)

- Decent work and economic growth (SDG 8)

- Industry, innovation and infrastructure (SDG 9)

- Sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11)

- Climate action (SDG 13)

- Life below water (SDG 14)

- Life on land (SDG 15).

Yet, there is significant underinvestment which, according to Reuters quoting the IMF, runs in the trillions of dollars annually:

Of the $5 trillion in annual investments needed globally by 2030 to meet net-zero emissions goals, $2 trillion will need to be made in emerging markets and developing economies.

The IMF’s GFSR estimates that the private sector will need to provide about 80% of these investments. This share rises to 90% when China is excluded, due to Beijing’s ample state resources.

The Fund’s Fiscal Monitor estimates that relying on public spending to fund de-carbonization investments on this scale would cause a massive, unsustainable run-up in debts, possibly to 45% to 50% of gross domestic product for a large, high-emitting emerging market.

(If this isn’t enough to convince you, read right to the end of this post for our collection of discouraging numbers.)

What are the more encouraging numbers?

- According to the IMF, a 1% increase in infrastructure investment leads to a 1.2% increase in GDP growth within four years.

- The average net benefit of investing in more resilient infrastructure in developing countries is $4.2 trillion globally, with $4 in benefits for each $1 invested, says the World Bank

- The World Bank suggests that public investment in infrastructure can have a “multiplier” effect (meaning measurable economic impact for each dollar of government spending), and that this effect is particularly high in the case of periods of crises.

Bottom line: more funding is needed for public investments, but almost equally, the quality of public investments need to improve.

This is important because the IMF estimates that countries waste anywhere from 30 to 50% of the money spent on infrastructure:

- 53% in low income countries

- 34% in emerging economies

- 15% in advanced economies.

Reducing this wastage and improving the quality of the resulting infrastructure through better investment practices will help build resilience and reduce the impact of all kinds of crises.

How can digital PFM help?

Governments and private sector partners have invested in capital projects for centuries, whether this has been for aqueducts, schools, railways, motorways, airports, or telecommunications.

Regardless of whether the end result is a bridge or a better broadband service, effective PFM improves small to large public investment quality.

We also know that using digital Government Resource Planning (GRP) systems optimizes public investment quality across all 15 elements of the Public Investment Management Assessment (PIMA) Framework.

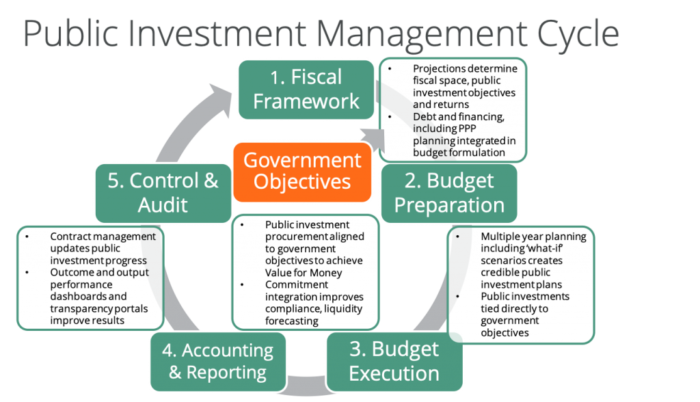

Effective PFM supports the public investment management budget cycle by:

- Aligning government infrastructure and social investment objectives directly to budget preparation

- Analyzing debt and financing requirements for credible budgets

- Planning contingencies based on risks and scenarios

- Integrating government objectives directly into Value for Money procurement methods

- Tracking output and outcome results through contract management integrated with SDG reporting

- Reporting procurement, output and outcome information transparently.

Why is this important?

Implementing effective PFM measures is important for two reasons:

- Effective PFM, as rated by Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability (PEFA) assessments is associated with quality public investment management

- Governments need to optimize investments from the Multilateral Development Banks.

Further, effective digital procurement tracks full lifecycle costs, including estimates for energy consumption. This enables further improvements so that public lighting, energy, transportation become green, data centres and cloud computing move towards net zero, and the Internet of Things (IoT) helps to track consumption and demonstrate progress. This data helps to improve future public investments, particularly in forming Value-for-Money calculations.

Of course, not everything is about digital. Policy changes help overcome perverse incentives.

What is the public investment gap?

Wondering how we get from where we are to where we want to be? Here are some of the references that we’ve collected over the years:

- The annual investment needed to achieve the 2050 targets will be around $5 trillion by 2030, especially in the countries with the highest carbon dioxide emissions, says the IMF

- Practically 70% of this capital will have to go to the energy sector, which faces the challenge of moving away from fossil fuels

- If financed with public capital, this amount would raise global public debt by between 45% and 50% of world GDP

- McKinsey estimates that meeting net-zero targets will require spending $9.2 trillion a year on physical assets between now and 2050, up from $3.5 trillion today

- $130 trillion is likely to be spent on projects to decarbonize the global economy and renew critical infrastructure (McKinsey)

- Few organizations are prepared to handle this capital influx with the speed and efficiency it demands, however, with many already struggling to deliver their existing capital programs.

- A recent survey of senior project executives found that, on average, projects overrun their budgets and schedules by 30 to 45 percent

- Governments spent $9.5T on infrastructure in 2015 says McKinsey, adding

- 14 percent of global GDP was invested in infrastructure in 2015

- There is a $5.5 trillion spending gap globally between now and 2035, with regional variations

- The overall spend estimate has risen from $3.3 to $3.7 trillion annually since the 2016 projection ,or $69.4 trillion total to 2035, due to an improved GDP growth outlook and a number of technical improvements

- There is a $15 trillion global infrastructure gap by 2040 according to Fasset, with $40 trillion required in infrastructure investment between 2020 to 2050 says GIH

- The White House estimates there is a $40 trillion infrastructure gap in developing countries

- [the cost of building sustainable energy infrastructure] could be as high as $3 trillion in annual investments needed by 2050…with 70% of the spending required in emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs), as reported by Infrastructure Outcomes

- The GIO says investment to the tune of $94 trillion is required in global infrastructure, but with $79 trillion investment, an gap of $15 trillion remains. Broken down by industry, this looks like:

- Energy: $2.9 trillion gap

- Telecommunications: $1.0 trillion gap

- Air transport: $530 billion gap

- Ports transport: $555 billion gap

- Rail transport: $1.2 trillion gap

- Road transport: $8 trillion gap

- Water: $713 billion gap

- Around $6.3 trillion of infrastructure investment is needed each year between now and 2030 to meet development goals, increasing to $6.9 trillion a year to make this investment compatible with the goals of the Paris Agreement says the OECD

- Roughly $1 trillion in additional spending is needed for developing countries to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals advises Brookings

- According to the United Nations, depending on the source used, sustainable development needs range between $80 trillion (World Bank Databank, 2017) and $200 trillion (Allianz Global Wealth Report, 2018). The report further notes that:

- Available finance is not channeled towards sustainable development at the scale and speed required to achieve the SDGs and goals of the Paris Agreement

- The financing gap to achieve the SDGs in developing countries is estimated to be $2.5 – $3 trillion per year

- The annual financing shortfall for agriculture was $11B in 2016, reports the World Bank

- The global investment needed for urban infrastructure is $4.5-$5.4 trillion per year, including a 9%-27% premium to make it low-emission and climate-resilient (World Bank)

- The UN estimates that the world needs $8.1 trillion investment in nature by 2050 to tackle the triple planetary crisis

- More than 4 billion people are still excluded from social protection, advises the ILO, explaining that:

- As of 2020, 53.1% of the world’s population had no access to social protection benefits at all, and 70.4% of the working-age population were not legally covered by comprehensive social security systems

- National social protection systems should be primarily financed from domestic resources

- The aggregate global digital infrastructure investment needed to provide universal broadband connectivity (SDG 9.c) is $418 billion, estimates the IMF

- UNCTAD estimates for the cost of delivering the SDGs in 48 developing economies breaks down to:

- Social protection and decent jobs

- $5.4 trillion annually, which is equal to $1,179/person, or 17% of collective GDP

- This leaves a spending gap of $294 billion annually

- Education transformation

- $5.4 trillion annually, or $1,300/person, comparable to 19% of collective GDP

- This leaves a spending gap of $275 billion annually

- Food systems

- $6.1 trillion annually, which works out to $1,342/person, or 20% of collective GDP

- An annual spending gap of $328 billion remains

- Climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution

- $5.5 trillion annually, $1,213/person or 18% of collective GDP

- The remaining spending gap equals $337 billion annually

- Energy transition

- $5.8 trillion annually, or $1,271/person, comparable to 19% of collective GDP

- This leaves a spending gap of $286 billion annually

- Inclusive digitization

- $5.7 trillion annually, equal to $1,231/ person or 18% of collective GDP

- A spending gap of $469 billion annually

- Gender equality

- $6.4 trillion annually, equal to $1,830/person or 21% of collective GDP

- Leaving a spending gap of $360 billion annually.

- Social protection and decent jobs

To stay up to date with our latest summaries of key developments in public financial management, subscribe to our newsletter

.