The Overseas Development Institute (ODI) convened a two-day Public Financial Management (PFM) conference. “Navigating the poly-crisis”, that attracted many practitioners and thought leaders last week (replay). This followed the International Consortium on Governmental Financial Management (ICGFM) conference the week before (our takeaways). Our takeaways from the ODI conference are:

- Polycrisis era requires public finance resilience

- Public finance resilience means using good PFM practices we know

- Increased digitalization for PFM efficiency and effectiveness

1. Polycrisis requires public finance resilience

Polycrisis background

The World Economic Forum Global Risks Report identifies potential crises clusters. Governments are at the nexus of addressing these risks. Realized risks have accumulated into polycrisis: “The generally recognised definition of a Polycrisis is the simultaneous occurrence of several catastrophic events. Building on this, most experts agree that it tends to refer specifically, not just to a situation where multiple crises are coinciding, but one where the crises become even more dangerous than each disaster or emergency on their own.”

Need for public finance resilience

Natural disasters, pandemics, climate change, inflation, inequality, conflict, currency and commodity price fluctuations places significant burden on public finances:

- Increased expenditures for social and business support

- Reduced revenue through inability to pay taxes

- Increased debt to meet expenditure needs

- Reduced fiscal space to handle the next crisis

ODI speakers and panelists described how the pandemic showed the need for fiscal resilience. The fiscal impact on governments from Covid-19 was much more than after the financial crisis of 2008. Among the concerning impacts are:

- Unequal recovery among countries and within countries

- Higher negative fiscal impact in poorer countries

- Disruption in spending on policy priorities and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Short-term crisis and recovery spending compromises investing in public finance resilience, Governments can leverage lessons learned from multiple crises to calculate the Net Present Value (NPV) of public finance resilience.

2. Public finance resilience means leveraging PFM good practices

The PFM that we know

Governments do not need new PFM tools, was the consensus at the conference. Well-understood PFM methods need to be leveraged more effectively. The integration of PFM good practices will be expressed in a soon-to-be-released updated handbook from the World Bank (1998 handbook).

Among the PFM observations from the conference were:

- Polycrisis requires multiple PFM interventions, rather than leveraging what seems to be most fashionable

- PFM performance progress has been uneven, as shown in Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability (PEFA) assessments (with some countries preventing public access)

- Primary PFM deficiency appears to be the lack of budget credibility in budget planning and controls

- Fiscal transparency is the best PFM governance lever, with many observers focused on the need for debt transparency, as described in a recent World Bank report

- World Bank to reimagine PFM. come up with a replacement handbook from 1998

Need to balance short with longer term policy objectives

Speakers identified ways to balance spending objectives by:

- Increasing taxes to mobilize domestic resources with care so that poverty is not increased in the short run

- Reorienting spending from general subsidies to targeted support for economic growth-education, health and infrastructure

- Focusing spending reviews on priorities rather than where cuts could be made

- Leveraging effective debt that generates returns with a good NPV, rather than debt that funds spending with poor service delivery outcomes

- Prioritizing spending for long-term growth, even in times of acute crisis

Public Finance resilience lessons

Government focus on long-term growth achieves public finance resilience. Social and infrastructure public investments with institutional reform enables resilience through:

- Improving the social safety net, reducing vulnerabilities, and achieving equity that reduces the burden on public finances when crises occur

- Overcoming the infrastructure gap to enable faster and better economic recovery

- Achieving climate adaptation and mitigation to reduce the number and severity of climate disasters and the resulting impact on public finances (demonstrating the NPV of climate finance)

- Leveraging financing alternatives through updated methods by multilateral development banks, ways of de-risking private investment, using carbon pricing, disaster insurance, blue and green bonds (although speakers warned that we need to spend 10x on climate & 10x on SDGs)

The Chartered Institute for Public Finance Accountancy (CIPFA) observed:

“In working towards increasing financial resilience, public sector organisations are faced with a number of hurdles.

- Increasing austerity: Over a decade of austerity and the impact of COVID-19 have significantly impacted the provision of services and, as inflation rises, the real value of budgets is further impacted.

- Shifting income sources: Income sources and funding for public sector bodies have been severely challenged by the pandemic. This makes strategic planning even more complex when planning how services need to be delivered.

- Changing demand patterns: Increasing demands on services, growing care costs, and changes to how we live and work as a result of the pandemic demonstrates the need for constant adaption in the provision of public services.

- Supply chain challenges: Rising demand for services creates pressure throughout the supply chain – from initial product procurement through to service delivery.

- The ongoing threat of bribery and corruption: Heightened by economic and social distress, as well as by increasing digitisation, the threat of fraud is increasing. A focus on fraud prevention is therefore key to help build financial resilience”

- Expenditures to achieve government outputs and outcomes is fundamental to public finance accounting

- Global and country climate change, fragility, and food security risks require government social and infrastructure investments.

- Benefits of tracking health spending and PFM for health was demonstrated during the pandemic, as was the importance of spending transparency

- Public spending integration with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is necessary to achieve objectives and track progress

Ultimately, governments should strive for what the World Bank calls shared prosperity and poverty reduction to achieve resilience. Among the research that supports this are:

- OECD Building Financial Resilience to Climate Impacts

- OECD Public finance resilience in the transition towards carbon neutrality

- World Bank & OECD Fiscal Resilience to Natural Disasters

Furthermore, the International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board (IPSASB) is developing sustainability accounting standards.

3. Increased digitalization for PFM efficiency and effectiveness

Finance ministry modernization

The consensus among most PFM experts and economists is that technology alone has little impact on improving governance. On the other hand, PFM legal reform often results in little governance improvement when informal processes remain dominant. As we observed from the ICGFM conference the previous week, significant public finance improvements require the combination of institutional modernization and digitalization.

The question of whether finance ministries should have a planning and policy role was answered at the conference in the affirmative. Only finance ministries deal with externalities while having a convening capability. No government official refuses a meeting invitation from finance ministers because these ministers control the money.

Finance ministries also participate in other levers like fiscal policy, fiscal rules, and regulation. It is finance ministries who should ensure that budgets are fully absorbed.

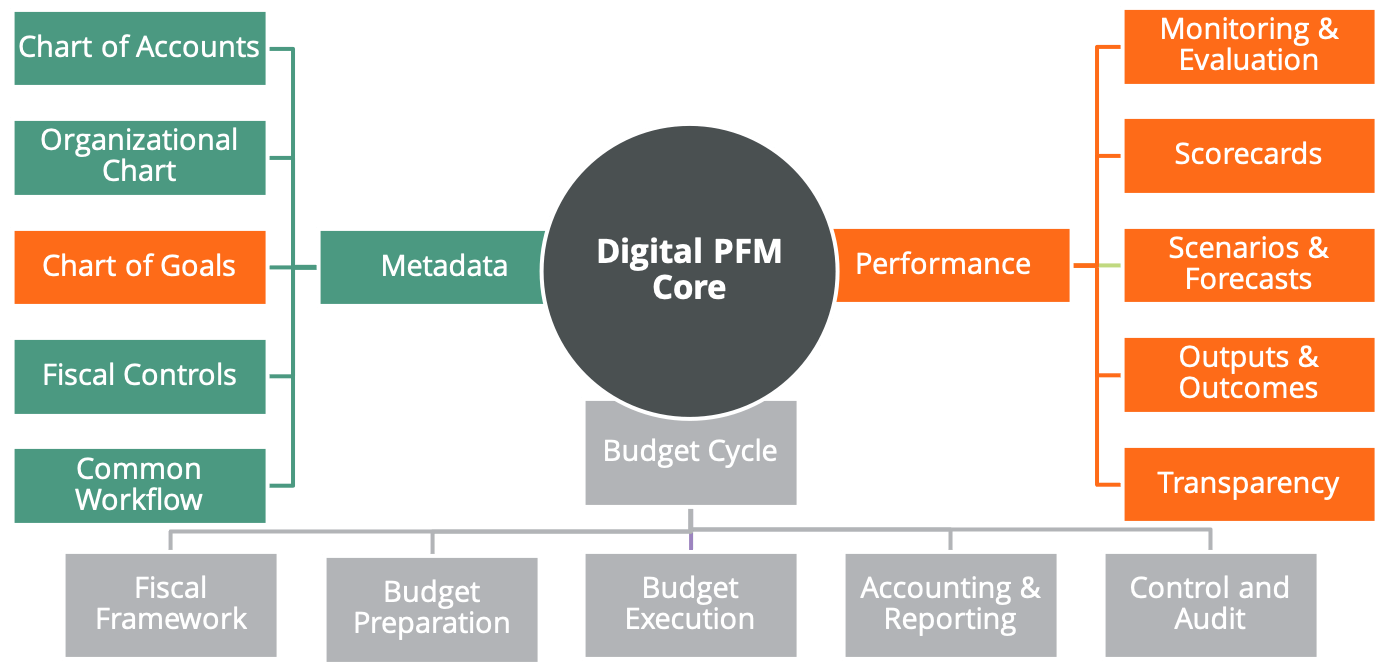

PFM digital transformation and interoperability

Finance ministries also have an important digital role. “A whole of-government approach requires its central institutions to act as standard bearers and as regulators for digitalisation (ODI paper).”

Digital PFM provides more efficient social support, service delivery, and fiscal transparency. This can be achieved through integrated controls and automation to achieve compliance.

Donors have an important supporting role because “lower-income countries have the most to benefit from this emerging digital PFM paradigm. Development partners need to adjust their funding models to be more supportive of emerging approaches to digitalisation (ODI paper).” We’ve seen many donors supporting PFM “silos”. There remains some understanding of integration and modularity.

“This prevailing paradigm is characterised by an unsuitable funding and delivery model, which contributes to a closed and siloed technology architecture. This is inseparable from a PFM system which is rigid and losing relevance.To be more flexible and responsive to users’ needs (policymakers, civil servants and citizens), PFM should embrace the new paradigm for digital government, its key principles – single source or truth, re-use and user-centricity – and ways of working (ODI paper).”

What we mean by interoperability:

- Metadata integration, such as Charts of Accounts, need to be augmented by consistent fiscal and commitment controls, supporting segregation of duties, to ensure quality data that followed compliant processes

- Performance criteria, such as V4M, needs to integrate with standard metadata, such as typing Charts of Accounts with Charts of Goals

- Budget cycle integration covers every PFM step, such as integrating budget and debt models or aid commitments with budget planning

Governments using open technologies and open architectures are more able to support systems of engagement and systems of intelligence from back-office financial systems to improve service delivery and decision-making. “This implies shifting to a much more open technology architecture in which digital solutions for PFM are part of a wider ecosystem of shared digital infrastructure, data and services (ODI paper).”

How to achieve PFM digital transformation

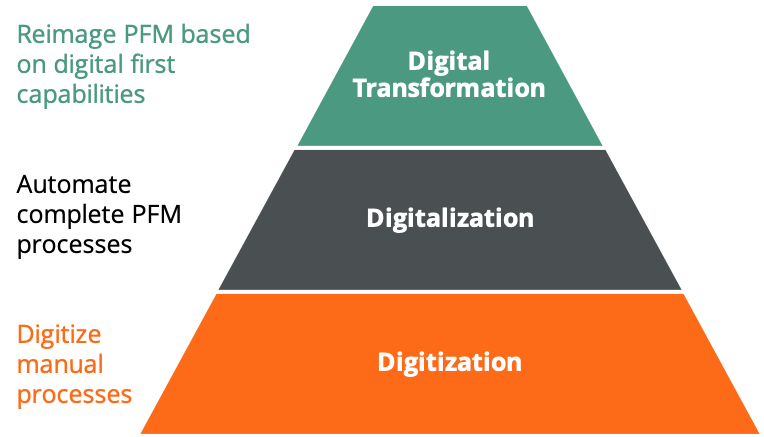

“Despite significant investments in IT for PFM, the prevailing paradigm has struggled to deliver successful digital transformation (ODI paper).” It’s no wonder because so many digital PFM projects focus on digitizing manual processes rather than rethinking.

Our digital approach recommendations align with the conference consensus and the work by ODI:

- Focus on outcomes to be achieved by PFM digital initiatives. “Governments need to reform their funding and delivery models to be more outcome-focused and problem-driven (ODI paper).”

- Recognize that interoperability supports evidence-based decision-making. “Data is the foundation for digital government. Improving data governance is fundamental for realising a digital revolution in public finance. As a community of practice, PFM is both a provider and user of government data, and it should set standards for itself and what it expects from others (ODI paper).”

- Traditional Information and Communication Technology (ICT) are not well-suited to transformation. Agile, iterative, user-centric methods are required. “This emerging paradigm for digital PFM recognises PFM and digital as means to an end, and PFM processes (and the digital solutions that underpin them) as requiring ongoing iterative redesign to remain flexible and responsive to users’ needs (ODI paper).” .

Other practices to consider in the PFM digital transformation journey include:

- Rational approaches to Cloud Computing

- Use of Low Code/No Code technologies

- Reduction in use of expensive Legacy Systems